Even my bosom friend in whom I trusted,

who ate of my bread, has lifted his heel against me.

-Psalm 41:9.

The common people worshipped Joan and were intoxicated by the victory and peace she brought. In contrast to such enthusiastic people, some of the French nobles and military commanders were jealous of Joan. Joan’s real enemies were among her allies, as Psalm 41:9 says.

The Gift of the Red Dress, and the Prediction

Near Châlons, on her way to Reims, Joan met with some friends who had arrived from the village of Domrémy. After spending a pleasant time with them, Joan was sent a red dress. Then she said something that seemed to foreshadow the tragic fate that awaited her; she told her two old friends that her only fear for the future was betrayal. (See: Gower, Ronald Sutherland, Lord, Joan of Arc. 1893.)

Was Joan simply telling her friends about her vague fears? Or was she receiving some kind of warning from God? Perhaps coincidentally, the red color of the dress that was sent to her is the liturgical color of a martyr. It seems as if it symbolized her death, as she followed God’s guidance to the end, and was burned.

In any case, this little episode foreshadowed the tragedy that was to take place in Compiègne.

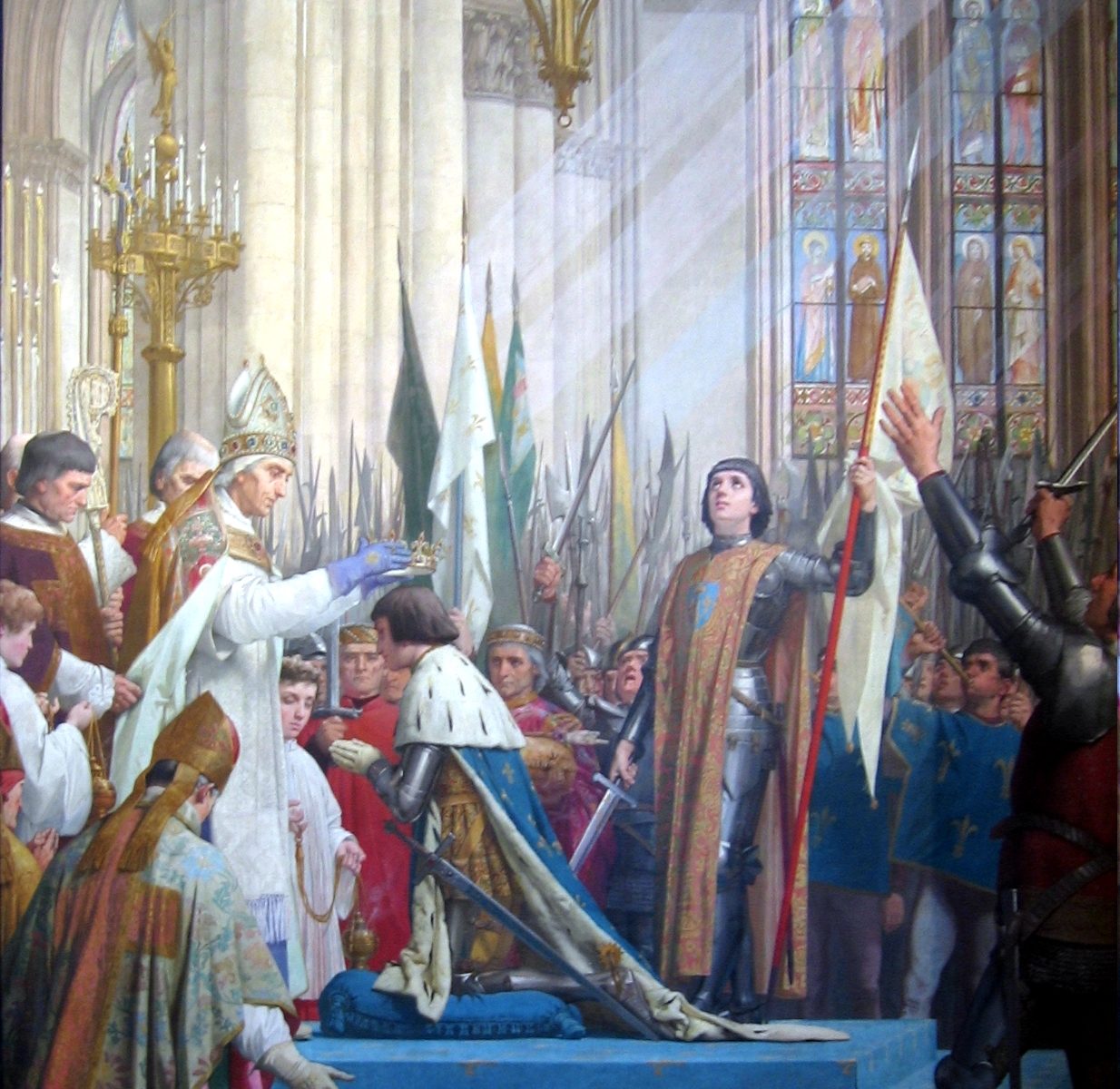

July 17, 1429: The Coronation of the King. Divine Prophecy is Fulfilled

The will of God, as Joan had told it to the king, had been fulfilled. Charles VII was finally crowned king.

The king entered the cathedral of Reims with the Maid of Orléans at his right hand. He was anointed and made King of France with the holy oil of the old abbey church of Saint-Rémy. Joan is said to have carried a banner and stood by the king’s side during the coronation.

It was not a tradition at a coronation ceremony for someone to hold a banner at the king’s side. The king, by allowing this breach of protocol, made it clear that he was still grateful for Joan’s achievement.

After the coronation, Joan is known to have knelt down, embraced the king’s feet, and proclaimed the following:

“Noble King, now is accomplished the pleasure of God, who willed that I should raise the siege of Orleans and should bring you to this city of Reims to receive your holy coronation, thus showing that you are the true King, him to whom the throne of France must belong.”

It is said that upon hearing these words, all those present (except the king) wept. From Joan’s words, we understand that she had no arrogance, and did not take credit for the king’s glory.

Joan’s wish for a place of eternal rest

“When I die, I should wish to be buried here among these good and devout people,”

she said. “I know not—it will come when God pleases; but how I would that God would allow me to return to my home, to my sister and my brothers! For how glad would they be to see me back again! At any rate,’’ she added, ‘‘I have done what my Saviour commanded me to do.” (Gower, Ronald Sutherland, Lord, Joan of Arc. 1893.)

The coronation was a success. And yet, in spite of all the pomp and circumstance, somehow she left the archbishop with words that sounded as if she had forebodings of her future.

Joan was speaking of her death and burial. At this time, she was still in her teens. At such an age, it seems unnatural for her to have been concerned with where she would be buried when she died. She went on to assert that the mission entrusted to her by God had been fulfilled.

Charles VII praised Joan’s achievements and made her, as well as her family, nobility, giving them a coat of arms and monetary rewards. According to Dr. Jeremy Adams, after the coronation, the king declared that Joan’s work was done and asked her to return to the countryside. Having accomplished her mission, she could have returned to her native village of Domrémy and lived a quiet life there, serving God as a nun. In fact, however, she chose a different path.

April 1430: Failure to Retake Paris

Joan believed that Paris had to be retaken to maintain the future security of France. But the people of Paris had already sworn allegiance to Henry VI of England. Fearing reprisals if the King of France took control of Paris, the people fortified the walled city’s defenses. Unfortunately, Joan’s troops were insufficient to attack a place with such strong walls and towers as Paris. The indecisive Charles VII finally sent more troops, and Joan launched an attack, but her army failed to retake Paris.

Joan was wounded in the thigh by a crossbow bolt, but remained on the battlefield. In the end, she had to retreat, against her will, but she protested that she would have won the battle if her troops had continued the attack.

Two Avengers—False Mouth, False Right Hand

Stretch forth thy hand from on high,

rescue me and deliver me from the many waters,

from the hand of aliens,

whose mouths speak lies,

and whose right hand is a right hand of falsehood.

-Psalm 144:7–8.

Joan’s failure to retake Paris delighted her enemies, who pretended to be her allies. Two enemies in particular, the Archbishop of Reims, and Georges de la Trémoille (c.1382 – 6 May 1446), influenced the king to put all the blame on Joan. As a result, the king authorized the Archbishop of Reims to conclude a truce with England, contrary to Joan’s wishes.

Regnault de Chartres (1380–1444)

The Archbishop of Reims at this time, Regnault de Chartres (1380–1444), was the very bishop who had heard the ominous words of foreboding from Joan at the coronation. Joan would not have thought that he was an enemy.

How did the archbishop feel when he heard Joan speaking about where she wanted to be buried after her death? No one knows. It is said, however, that later, when Joan was captured, the archbishop was overjoyed, saying that it was proof of God’s justice. He was also the one who brought the news of Joan’s capture to the people of Reims, telling them that Joan was proud and had incurred God’s wrath by trying to follow her own will rather than God’s.

Georges de La Trémoille (1382 – 1446)

The other main adversary of Joan was a nobleman named Georges de la Trémoille (c.1382 – 6 May 1446). He was distantly related to Gilles de Ré, a loyal follower of Joan who later became known as a murderer. La Trémoille, through his shrewdness, had a great influence on Charles VII. His cruelty can be seen in the fact that, merely for his personal financial gain and status, he kidnapped and drowned Pierre de Jacques, who had been one of Charles VII’s favorites.

He had done everything in his power to keep the king from going to Reims. He also thwarted Joan on various occasions, and when she wanted to attack Paris again, he prevented her from doing so. It is said that his influence was also responsible for the king’s failure to obtain Joan’s release when she was later captured.

Joan’s Dark Fate Spelled Out by Her Voices

Joan’s voices no longer gave her any clear commands as they once had done, but she continued to fight to save France.

In early April 1430, while Joan was in the town of Melun during Easter week, St. Catherine and St. Margaret spoke to her telling her that she would be taken prisoner before St. John’s Day (June 24), but not to fear. It is said that she asked of the saints that, when she was captured, she might die immediately. The Battle of Jargeau 12 Jun 1429 (jeanne-darc.info)

After this, Joan decided to go to the battle of Lagny-sur-Marne. Even the fear of possible capture did not dampen her burning desire to save France. Joan of Arc | Biography, Death, Accomplishments, & Facts | Britannica

April 1430: The Battle of Lagny-sur-Marne: The Beheaded Man

The Burgundians, on the side of the English, had assembled a large force at Arras to reinforce their defense of Paris. The Burgundian army was led by Franquet of Arras, who was heading for Lagny. However, on their way to Lagny, they sacked another city, alerting the French to the danger and allowing them to prepare for battle.

Thanks to the troops at Lagny, French reinforcements, and the efforts of Joan and her men, Franquet of Arras was captured, and his men were either killed or taken prisoner. Franquet was then supposed to have been exchanged for a prisoner of war that Joan wanted, but it turned out that that prisoner was already dead. Moreover, it was revealed at his trial that Franquet of Arras was guilty not only of plunder, but also of murder. Asked what to do with him, Joan told her men, “Do with this man as justice demands.” The Battle of Jargeau 12 Jun 1429 (jeanne-darc.info)

God has mercy on human sin.

Joan was not specific about the punishment that justice demanded. The punishment that Franquet received was beheading. Later, the beheading of Franquet would be a determining factor in Joan’s fate: the Inquisition held Joan responsible for it, and it was one of the reasons for her execution by fire.

Was the execution of Franquet justified? Well, on the one hand, he was tried by a jury and found guilty of murder, and the penalty for murder, in those days, was death. On the other hand, as a prisoner of war, he was entitled to some rights, including, it could be argued (but this is a gray area), the right to be returned to his own nation, to be tried there by a jury of his fellow-countrymen.

The Bible says, “But God shows his love for us in that while we were yet sinners Christ died for us” (Romans 5:8).

We do not know how much responsibility Joan bore, in God’s eyes, for the beheading of Franquet. But if she had had compassion on him, as Christ had compassion on us sinners, Franquet would have had a chance to survive.

May 23, 1430: Joan captured at the siege of Compiègne

The final battle of Joan’s life was the siege of Compiègne on the Day of Pentecost. In theory, to engage in battle on a Sunday, let alone a major Holy Day such as Pentecost, was forbidden by the Peace and Truce of God, a set of rules which had been established throughout Europe, beginning in the 10th Century, to regulate and limit the conduct of warfare. By the 15th Century, however, the Peace and Truce of God was being ignored by pretty much everyone. (While researching this topic, I was surprised to learn that the spirit of secularism was already so widespread in the mid-fifteenth century.) Perhaps Joan did want her army to fight on the holy Feast of Pentecost; perhaps her army insisted on doing so in spite of her wishes. We will never know.

At any rate, Joan, with about 500–600 cavalry and infantry, attacked the Dukes of Burgundy. During the battle, Joan was dragged off her horse by an archer, and taken prisoner by the Burgundians. It is said that the English and Burgundians were more pleased with the capture of Joan than they were with the capture of 500 soldiers. (See: The campaigns of Joan of Arc, according to the Chronicles of Enguerrand de Monstrelet (deremilitari.org))

Once captured, Joan was placed under the guardianship of John II de Luxembourg (1392–1441). His aunt (also named Joan), known as the Demoiselle de Luxembourg, was sympathetic to Joan, and opposed selling her to the English. She threatened to cancel her nephew’s inheritance if he did so.

Joan sold to England

Her sympathy for Joan may have been due to the fact that she, like Joan, was very devout. Unfortunately for Joan, in 1430, the Demoiselle visited Avignon to pray at the tomb of her brother Pierre, and, while there, died.

The Demoiselle’s brother, Pierre de Luxembourg, who had been a Cardinal at Avignon until his death in 1387, was considered by some to be a saint (he was eventually beatified by Pope Clement VII in 1527).

John II, no longer worried about his inheritance, sold John to the English in exchange for a ransom. He ignored the terms of his aunt’s last will and testament, which stipulated that he would not sell Joan to the English in exchange for a ransom. John II had acquired a vast fortune. However, he never spent it, for he died the following year.

Joan had a series of fortunate moments in quick succession, up until the coronation of King Charles VII. After that, however, a dark shadow seems to have been cast over her life. Again and again, Joan found herself in situations where she should have been set free; again and again, she was betrayed.

Image: Joan in Reims Cathedral by Jules-Eugène Lenepveu